When we think of Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), the color gold immediately comes to mind. His canvases, more than paintings, look like gigantic jewels, shimmering mosaics that merge the human figure with abstract patterns and metallic flashes. But this love for gold was neither accidental nor a passing fad; it was a direct inheritance, a vocation forged in his childhood workshop. To understand the artistic revolution that Klimt led in Vienna, we must first get to know the man who dreamed in gold.

The Legacy of the Craft: A Goldsmith as a Father

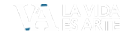

Gustav Klimt was born in Baumgarten, near Vienna, in 1862. His family environment was crucial. His father, Ernst Klimt, was not a painter, but a gold engraver and goldsmith. In the Klimt home, the air did not smell of pigment and turpentine, but of metals, acids, and the luster of gold being worked with fine tools.

Young Gustav grew up observing his father's meticulous work: the precision of engraving, the detail of filigree, and, above all, the art of transforming a raw material into an object of pure beauty. This influence is key to understanding his work. While other artists focused on capturing light and shadow realistically, Klimt sought the **texture, pattern, and inherent luxury of the material**. He did not paint gold objects; he painted *with* gold, treating the paint as if it were enamel or inlay on metal. He studied at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts and, together with his brother Ernst and Franz Matsch, founded the "Company of Artists," undertaking large decorative commissions following the prevailing academic style.

The Golden Break: Leading the Vienna Secession

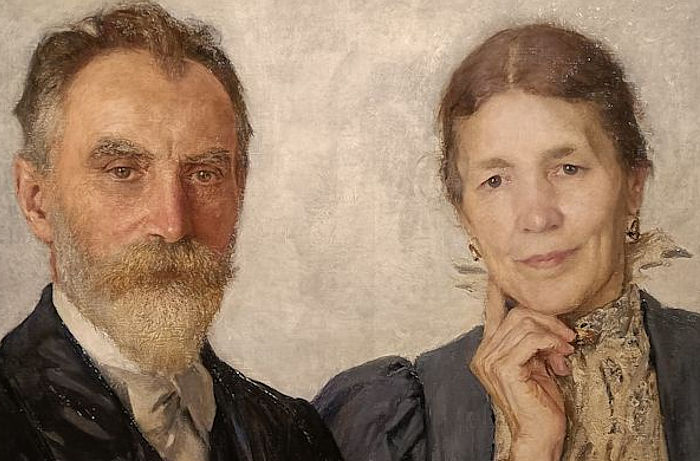

In the late 19th century, the Viennese art scene was stagnant in academic conservatism. Klimt, already a successful artist but increasingly frustrated by restrictions, felt the need to break the rules. In 1897, he led a group of artists and architects who left the Association of Austrian Artists to found the **Vienna Secession**.

The motto of this Modernist movement was: *"To every age its art, to every art its freedom."* The Secession sought not only a new style but an ideal: the *Gesamtkunstwerk*, or "total work of art," where painting, architecture, and applied arts merged. It is in this context of freedom and experimentation that Klimt developed his characteristic **"Golden Period."** His art focused on themes of love, death, sex, and the unconscious, themes that resonated with the flourishing psychoanalytic culture of Sigmund Freud's Vienna.

Five Masterpieces That Define Klimt's Legacy

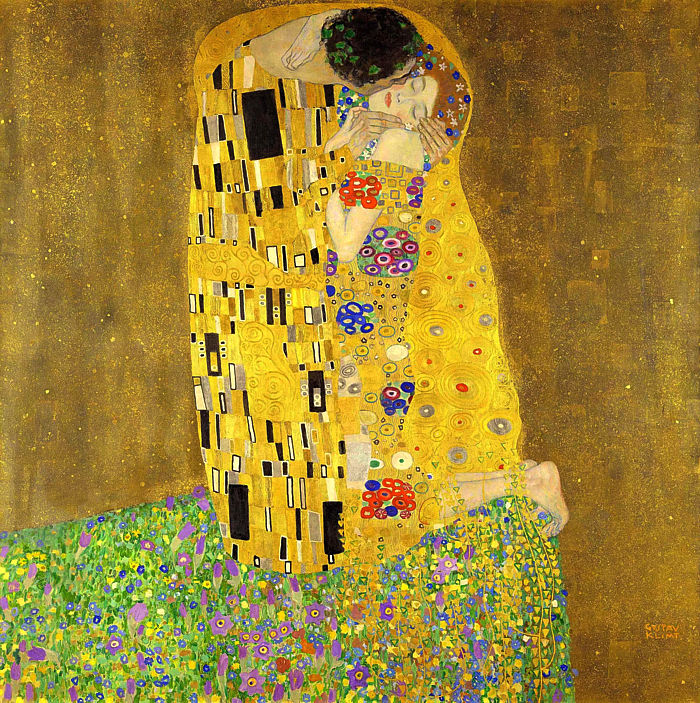

1. The Kiss (Der Kuss) (1907-1908)

If there is one work that defines the Golden Period, it is "The Kiss." The painting shows a couple embracing in a flower meadow, but their bodies are almost completely enveloped in shimmering gold robes, treated like mosaics. The man is covered in austere rectangles, symbolizing male strength. The woman, on the other hand, is adorned with circular and floral patterns, representing female energy and ecstasy. The man's face is hidden, drawing the viewer into the intensity of the moment, while the woman appears to be in a state of passive ecstasy. Gold is not just a color; it is a **cloak that isolates the couple from the world**, creating an intimate, timeless universe. It is the definitive representation of absolute passion.

2. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907)

Also known as "The Woman in Gold" (of which we spoke in our previous article), this is the zenith of Klimt's pictorial goldsmithing. Adele Bloch-Bauer, a wealthy Jewish patron and friend of Klimt, is portrayed as a Byzantine goddess. Adele's figure almost disappears in a sea of symbols, where thousands of tiny squares and triangles of engraved gold and silver leaf cover her dress and the background. Klimt's father would have taught him the technique of *repoussé* (working metal from the reverse), and Klimt applied a similar concept, treating the canvas as if it were a metal plate to be decorated. The work is famous not only for its beauty but for the dramatic story of its theft by the Nazis and its subsequent restitution.

3. The Beethoven Frieze (Beethovenfries) (1902)

This monumental frieze was created for the Vienna Secession Exhibition in honor of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven. The work, with its strong allegorical charge, represents the journey of the human soul in search of happiness. It is divided into three sections: the aspiration for happiness, the hostile forces (including the famous Typhon gorilla and Sickness), and liberation through art and love (culminating in a kiss). The striking feature of the frieze is its linear, almost two-dimensional design, reminiscent of decorative reliefs. The use of gold is more sporadic than in "The Kiss," but serves to highlight the allegorical figures, such as Poetry and Music, showing how Klimt could integrate his figures into an architectural context.

4. Danaë (1907-1908)

In Greek myth, Danaë is seduced by Zeus, who appears as a shower of gold. Klimt takes this mythological scene and transforms it into an image of intense sensuality. Danaë is depicted in a fetal position, curled up and absorbed in ecstasy. The "shower of gold" is a cascade of small golden rectangles falling upon her, symbolizing divine conception. This work is an example of how Klimt used mythology to explore femininity, desire, and sexuality in a way that was radical for his time, combining the classic theme of *La vida es Arte* with his bold modernism.

5. Death and Life (Tod und Leben) (1910-1915)

This work addresses the eternal human duality. On the left, Death, depicted as an austere skeleton covered by a cloak of crosses. On the right, Life, a group of human figures (men, women, and children) embracing, symbolizing the inescapable cycle of existence and the continuity of life despite the constant presence of Death. In this painting, Klimt begins to move away from the gold excess of his previous period, using softer colors and a darker background. The contrast is intentional: Death is dark and geometric; Life is organic and full of colorful patterns, a tapestry of flesh and cloth clinging to the present moment. It is a powerful meditation on the fragility and beauty of our brief existence.

The Unalterable Legacy of the Brush's Goldsmith

Gustav Klimt died in 1918, a tragic year for Vienna and for the art world, where Egon Schiele and Otto Wagner also passed away. Although his Golden Period was relatively short, its impact was seismic. By incorporating his father's craftsmanship technique and mindset into high painting, Klimt elevated decoration to the status of sublime art.

His work is a bridge between 19th-century academic art and 20th-century Modernism. He stripped bare the taboos of Viennese society, wrapped the human psyche in a mantle of Byzantine gold, and, in doing so, created a visual universe that remains overwhelmingly beautiful and an inexhaustible source of fascination. Klimt's art reminds us that beauty, sensuality, and history can merge into a single, radiant, and eternal "Golden Kiss."