Hades, called Pluto by the Romans, was the god of the Greek underworld, the land of the dead in Greek and Roman mythology. While some modern religions view the underworld as hell and its ruler as the embodiment of evil, the Greeks and Romans saw the underworld as a place of inescapable darkness. Though hidden from daylight and the living, Hades himself was not evil. Instead, he was the guardian of the laws of death, a somber but rigorously just sovereign.

The god of the underworld was known by many names: Zeus of the underworld (due to his divine rank), Aïdes (the unseen, for the helmet that made him undetectable), Pluto (the giver of wealth, a euphemism referring to the treasures that come from the earth), Polydegmon (the hospitable, for there is always room for one more soul), Euboueus (wise in counsel), or Klymenos (the renowned ruler of the dead).

According to Greek mythology, Hades was one of the sons of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. His other siblings included Zeus, Poseidon, Hestia, Demeter, and Hera. Upon hearing a prophecy that his children would overthrow and murder him, Cronus devoured all but Zeus, as we have recounted before in La vida es Arte. Zeus managed to force his father to vomit up his siblings, and the gods embarked on the great war against the Titans, the Titanomachy. After winning the war, the three major brothers drew lots to determine who would rule over the sky, the sea, and the underworld. Zeus became the ruler of the sky, Poseidon of the sea, and Hades of the underworld; and, of course, Zeus also maintained his role as King of the Gods.

After receiving control of his kingdom, Hades withdrew and, living an isolated existence, had little to do with the world of living humans or gods. Although he rarely appears in Greek art, when he does, Hades carries a scepter or a key as a sign of his authority; the Romans illustrate him carrying a cornucopia, symbolizing subterranean riches. He is often seen as an angry version of Zeus, and the Roman Seneca described him with "the aspect of Jupiter, but when he thunders." He also possesses a helmet of darkness that he uses to hide in the shadows.

In both Greek and Roman mythology, and despite the different names, Hades is the ruler of the dead, gloomy and sorrowful in character, and severely just and inflexible in the performance of his duties. He is the jailer of the souls of the dead, keeping the gates of the underworld locked and ensuring that dead mortals who entered his dark realm never escape. He only left the realm himself to abduct Persephone as his wife; and none of his fellow gods visited him except Hermes, who ventured in when his duties required it.

The Topography of the Greek Underworld: Not the Christian Hell

A terrifying but not malevolent god, Hades had very few worshippers on the surface. While the underworld was the land of the dead, there are several stories, including Homer's The Odyssey, in which living men go to Hades and return safely. When the god Hermes delivered souls to the underworld, the ferryman Charon transported them across the River Styx. Upon reaching the gates of Hades, souls were greeted by Cerberus, the terrible three-headed dog, who would allow souls to enter the place of mist and darkness but prevent them from returning to the land of the living.

The crucial difference from the Christian Hell is that Hades was the destination of all souls, regardless of their morality. In some later myths, the dead were judged to determine the quality of their lives. The underworld was divided into sections:

- The Elysian Fields: For those considered good people and heroes. They drank from the River Lethe to forget all bad things and spend eternity in a place of perpetual bliss.

- Tartarus: A deep prison, surrounded by bronze, reserved for Titans and those who had committed heinous crimes against the gods (like Sisyphus or Tantalus). This was the closest version to the concept of a "hell."

- The Asphodel Meadows: The destination for common souls, neither especially good nor bad, where they led a gray, purposeless existence.

The main myth associated with Hades is how he obtained his wife, Persephone, a myth we have already recounted in detail. But there are other myths that demonstrate his power, such as the labor of Heracles, who had to bring Cerberus back from the Underworld, or the failed attempt by Theseus and Pirithous to abduct Persephone, which ended with both trapped on the Seats of Forgetfulness until Heracles rescued them.

The Divine Comedy: A New Vision of Hell

Mythology and sacred books were not the only literary sources of inspiration for painting. Epic poems have also been a genre that generated great works. Dante's Inferno, the first part of The Divine Comedy (written in the early 14th century), is an epic poem recounting Dante Alighieri's journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, guided initially by the Roman poet Virgil. Unlike the Greek Hades, Dante's Hell is a moral structure, designed to punish every human sin with an appropriate torment, creating a topography of terror organized into nine concentric circles.

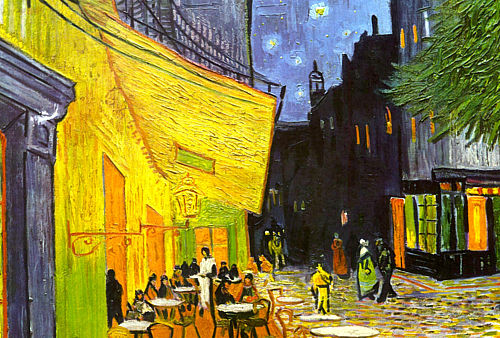

The Divine Comedy became an inexhaustible source of inspiration for artists of all eras, from the illustrations of the original poem to actual paintings of different styles and techniques. One of the most outstanding, and the one we analyze here, is this magnificent work by William-Adolphe Bouguereau.

Bouguereau and Academic Virtuosity

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) was a master of French Academic painting, known for his idealized realism and impeccable technique. His work, painted in 1850 and officially titled Dante and Virgil in Hell, is a striking example of how 19th-century academic art turned to literature to create scenes of high drama and technical virtuosity.

The scene takes place in the Eighth Circle of Hell (Malebolge), reserved for falsifiers and imposters. Bouguereau captures a specific and particularly brutal moment recounted by Dante: the fierce attack of Gianni Schicchi (an Italian imposter condemned for falsifying a dead man's identity) on Capocchio (a famous alchemist condemned for counterfeiting). It is a scene of cannibalistic rage and animalistic fury.

The composition is designed to maximize horror. In the center, the nude bodies of the two condemned men writhe in a savage struggle. The exaggerated posture and torsion of the bodies are a demonstration of Bouguereau's mastery of classical anatomy. The perfect representation of form and muscle tension, the fierceness of the faces, the flesh torn under the attacker's grip, the veins swollen under the enormous physical exertion—all testify to this painting, which is simultaneously horrifying and extremely beautiful. The pictorial realism in the depiction of the two bodies, which the viewer's eyes instinctively look at, is of cinematic excellence.

To one side of the scene, as observers and judges, stand the two poets. One can see the terror on Dante's face (the man in the red and black suit in the back), a mortal overwhelmed by the horror of divine punishment. In stark contrast, his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, appears quite indifferent to the fight, maintaining composure and reason, reflecting his status as a classical guide and a symbol of human reason, unmoved by emotional chaos. In the background, tormented and suffering souls can be seen, along with a smiling, cross-armed devil flying overhead, adding a macabre touch.

Dante and Virgil was the first major work Bouguereau exhibited at the Paris Salon. Although he is now better known for his delicate paintings of nymphs and children, this early work demonstrated his enormous talent for historical painting and the ability to create scenes of great pathos. The work merges medieval literary iconography with the neat technique and anatomical virtuosity of Academicism, creating an unforgettable image of divine justice through punishment. The contrast between the serene malice of the Dantesque Hell and the cold justice of the Greek Hades is a lesson in history and philosophy that only art, across the centuries, can impart.

THE WORK

Dante and Virgil (or Dante and Virgil in Hell)

Artist: William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Medium: Oil on canvas

Date: 1850

Location: Musée d'Orsay, Paris