In the heart of the ocean, where the sunlight surrenders to the dominion of the deep blue, the young fisherman feels the cold, damp touch of the syren. Her fingers slide across his skin with a deceptive, almost electric softness, while he ignores the fatal destiny looming over his head. He is lost, absolutely hypnotized by the spell of eyes that do not belong to this world. Time seems to stop in an eternal sigh as she wraps him in one last embrace; her lips, so close to his, whisper promises of love and submerged kingdoms that will never be fulfilled. In that single, fatal moment, his humanity begins to dissolve into the absolute abyss.

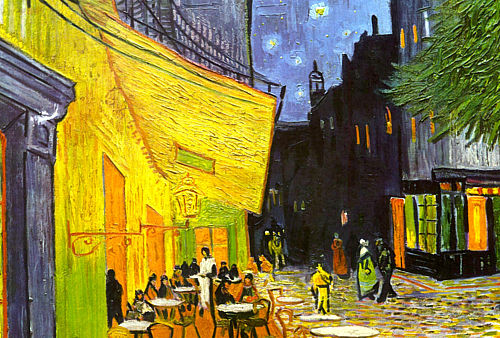

The syren, without a trace of remorse in her glassy gaze, drags him toward the dark bottom, sealing a fate from which there is no return. Her love is not a gift, it is a deadly trap; and he, blind to the truth beating beneath the scales, gladly succumbs to her eternal charm. This image, masterfully captured by Frederic Leighton, plunges us into one of the most persistent and disturbing myths of our collective history.

Syrens have captured the human imagination since the first man peered into the vastness of the sea. They have appeared in mythologies, legends, and literary works of almost every culture, evolving from the terrifying monsters of ancient Greece to the melancholic and tragic figures of Romanticism. Let us explore the fascinating and dangerous history of these "girls of the sea" throughout the centuries.

Roots of Feathers and Scales: The Greek Origin

Although today we imagine them with long fish tails, the original syrens of Greek mythology were very different. They were known as the "Merides," creatures with the upper half of a woman and the lower half of a bird. They were the daughters of the muse Terpsichore and inhabited rocky islands, waiting for ships to pass. The most famous are those mentioned in Homer's "Odyssey." Odysseus, warned by the sorceress Circe, had to plug his men's ears with wax and have himself tied to the mast of his ship to listen to their song without throwing himself into a certain death.

Those Greek syrens did not attract with promises of sex or romance, but with absolute knowledge: they promised to tell the traveler everything that had happened on earth. They were intellectually seductive and physically lethal beings, as their ultimate goal was to devour the sailors once they ran aground on the rocks. It was this story by Homer that established the archetype that has endured: beauty as a facade for extreme danger.

Over time, in Roman mythology, these creatures blended with the Nereids, the fifty daughters of Nereus and Doris—marine divinities who, unlike the Greek syrens, were usually benevolent and helped sailors in distress. However, popular culture preferred to stick with the dark side of the legend, merging the fish tail of the marine deities with the lethal voice of the bird-women.

The Middle Ages: The Syren as Sin

During the European Middle Ages, the figure of the syren took a radical turn. The Christian Church adopted them as a moralizing symbol. In illuminated manuscripts and on the capitals of Romanesque churches, the syren became the personification of carnal temptation and the seduction of the material world. They were malevolent beings that tried to divert the faithful from the "straight path" toward salvation.

In this period, it was common to see representations of twin-tailed syrens (like the famous logo of a well-known coffee chain), symbolizing duplicity and deceit. It was said that their song was not music, but the echo of the vices that drag man to hell. The duality of beauty and danger remained, but now loaded with an ethical weight: to look at the syren was to fall into sin.

The Far East and the Renaissance

While Europe feared its syrens, other cultures developed their own myths. In Chinese mythology, for example, there are the "Jiaoren," aquatic beings whose tears turned into pearls and who had the amazing ability to weave a very fine silk called "dragon silk." Unlike their Western cousins, the Jiaoren were often seen as wise beings who could predict the future and warn sailors of impending storms.

With the arrival of the Renaissance, interest in classical mythology resurfaced with force. Artists no longer saw the syren only as a symbol of sin, but as an object of aesthetic beauty. Painters like Botticelli began to populate their canvases with sensual marine beings, half-human and half-fish, recovering the elegance of classical forms. It was during this time that the image of the syren with a mirror and comb became popular, symbolizing her vanity and her power to catch a man's eye.

Romanticism and Andersen's Tragedy

We reach the 19th century, the era of Romanticism, where the syren acquires her deepest and most melancholic dimension. Romantic writers were obsessed with wild nature and the mysterious. For them, the syren represented the connection to the unexplored and the forbidden. In 1837, Hans Christian Andersen published "The Little Mermaid," a work that changed the perception of the myth forever.

Andersen introduced us to a compassionate mermaid, capable of love and sacrifice. She was no longer a soulless predator, but a being who yearned for immortality and a human soul. This softer vision coexisted with that of the Symbolist poets, who preferred to see in them the eternal struggle between wild instincts and reason. The syren became the ultimate "femme fatale": one who is so beautiful that she makes death seem a fair price for a single kiss.

Work Analysis: The Master Frederic Leighton

It is in this Romantic and Symbolist context that Frederic Leighton's "The Fisherman and the Syren" was born in 1861. Leighton, one of the most influential figures in Victorian art, offers us a scene charged with an almost unbearable sensuality. There is no explicit violence, but the tension is at its peak.

Observe the fisherman: his face is lost in thought, his closed eyes say it all. He is not fighting; he has surrendered. His pose is that of someone who has handed over his will to desire. On the other hand, the syren embraces him with possessive force, clinging to his neck as she lifts him slightly, preparing him for the final descent. The contrast between her pale skin and the young man's tanned body accentuates the difference between the two worlds colliding in this embrace.

Leighton uses exquisite brushstrokes to detail the seaweed that, like snakes, surrounds the sailor's neck, and the white foam that seems to kiss his lips. It is a scene of total seduction where the fisherman, seduced and trapped, is willing to die to have for a few moments the beauty and impossible love of this creature. The painting tells us that, in the face of absolute desire, survival takes a backseat.

The Syren in Today's Popular Culture

Today, syrens continue to swim in our collective imagination. From Disney's sugar-coated versions to darker interpretations in contemporary television series and horror films, the duality persists. We remain fascinated by the idea of a being that belongs to two worlds and that reminds us that, beneath the surface of our rational civilization, ancient and dangerous instincts still beat.

The ability of these creatures to evolve and remain relevant is a testament to the powerful influence of myths. They speak to us of our relationship with the unknown, of our fear of the abyss, and of our eternal search for beauty, even when we know that beauty can be our downfall.

If you want to see how other geniuses of the brush have interpreted this myth, do not miss the video accompanying this article, where you will find works by various artists who, like Leighton, fell under the spell of the girls of the sea.

THE WORK

The Fisherman and the Syren

Artist: Frederic Leighton

Technique: Oil on canvas

Size: 66.3 cm x 48.7 cm

Year: 1861

Location: Private collection