A young family enjoys a tender moment in a lush clearing. Venus, the goddess of love, holds the bow of Cupid, her son, while his father Mercury, the god of wisdom and messenger of the gods, teaches him to read. Mercury looks at his little one with an almost human affection, but Venus breaks the fourth wall: she gazes at us dreamily and smiles, inviting us to be accomplices in this divine domestic scene. Unusually, in this depiction, Venus is shown with wings, a detail that has puzzled and fascinated historians for centuries.

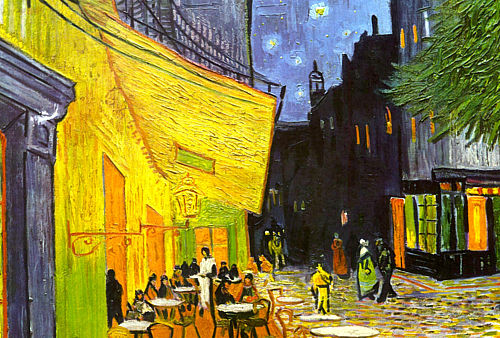

The painting was designed as a pair (pendant) alongside another masterpiece: Venus and Cupid discovered by a Satyr. In this second piece, a satyr stealthily pulls back the cloth covering a deeply sleeping Venus and Cupid, revealing their naked bodies stretched out in a state of voluptuous abandon. While the Louvre painting represents the terrestrial Venus and a more instinctive love, the work in the National Gallery in London represents the celestial Venus and the education of the spirit. Both images were intended to be displayed together, and a 1589 inventory records that they were hung in a ground-floor bedroom of a palace in Mantua, creating a visual dialogue between physical and intellectual love.

The Education of Cupid was always an extremely famous work, whose elements have been studied and copied by giants such as Titian, Annibale Carracci, and Rubens. It was painted by Antonio Allegri da Correggio on a commission from Federico II Gonzaga, as part of an ambitious group of mythological works intended to decorate his most private rooms with the highest artistic sophistication of the time.

The Education of Cupid: Wisdom and Sensuality

In "The School of Love," Correggio achieves something almost impossible: endowing a pedagogical scene with a subtle yet omnipresent erotic charge. The figure of Mercury is not that of a stern god, but that of a patient father. The fact that the god of commerce and eloquence is teaching the god of desire to read suggests that love, to be complete, must be guided by reason and communication. However, the presence of Venus, completely nude and winged, reminds us that desire is always present.

Correggio's technique is the main protagonist here. Heir to Leonardo da Vinci's *sfumato*, Correggio takes the softness of light transitions to an almost tactile level. The bodies have no hard outlines; they seem to melt into the humid and shadowy atmosphere of the forest. This delicacy and the use of pearlescent colors are what lead many critics to see Correggio as an artist who was two centuries ahead of his time, anticipating the aesthetics of the French Rococo and 19th-century Romanticism.

The Mystery of the Satyr and the Sleeping Venus

Regarding "Venus and Cupid discovered by a Satyr," we are faced with one of the most powerful allegories of earthly love. For a long time, it was believed that the female figure was Antiope of Thebes. According to myth, Antiope was a mortal of legendary beauty who caught the eye of Zeus, who decided to seduce her by taking the form of a satyr. Traditionally, the painting was considered to capture the exact moment when Zeus stalks the sleeping woman.

However, modern criticism leans toward identifying the protagonist as Venus. The key lies in the torch lying between her and Cupid, a traditional symbol of the goddess of love and not the Theban princess. Furthermore, the fact that her son Cupid rests by her side reinforces this theory. Here, love is vulnerable, exposed, and observed by an instinctive and wild force represented by the satyr.

It is a typical work of early Mannerism, where the perfect balance of the High Renaissance begins to dissolve. The figures are no longer arranged in a stable pyramid; instead, they adopt twisted poses (the famous *linea serpentinata*) and are placed diagonally, forcing perspective and increasing the sense of depth and drama. The satyr's body, muscular and sculptural, inevitably recalls the titanic figures of Michelangelo, but softened by that fleshly warmth that only Correggio knew how to imprint.

Correggio and the Architecture of Light

To understand the importance of these Venuses, we must look beyond the mythological theme. Correggio was a master at creating psychological spaces. In "The Education of Cupid," the light falls from above, illuminating Venus's white skin in a way that makes it stand out against the dark foliage, almost as if she were a source of light herself. This technique allowed the paintings to glow even in the poorly lit rooms of Renaissance palaces.

The influence of these works on art history is incalculable. When 19th-century artists took the famous "Grand Tour" through Italy, Correggio's works were mandatory stops. They admired his ability to paint flesh not as a solid surface, but as something alive that reacts to light and touch. Artists like Titian learned from him how to breathe soul into mythological themes, moving them away from the coldness of statues to turn them into beings of flesh and blood.

The Legacy of a Discrete Genius

Antonio Allegri, known by the name of his hometown, Correggio, was an artist who worked far from the major centers like Rome or Florence for much of his life, but his impact was global. His Venuses are not just depictions of goddesses; they are studies of intimacy, vulnerability, and beauty. By separating love into its two aspects (the educational and the instinctive), he left us a visual testament to the complexity of human emotions.

Today, observing these two paintings—one in London and the other in Paris—we reconnect with that romantic and sensual vision that challenged the conventions of its time. Correggio taught us that art serves not only to narrate myths, but to make us feel the warmth of a caress or the peace of a deep sleep under the gaze of a stranger.

THE WORKS

1) The Education of Cupid (The School of Love)

Artist: Antonio Allegri da Correggio

Date: c. 1525

Technique: Oil on canvas

Size: 155.6 x 91.4 cm

Location: National Gallery, London

2) Venus and Cupid discovered by a Satyr

Artist: Antonio Allegri da Correggio

Date: c. 1524-1525

Technique: Oil on canvas

Size: 188 × 125 cm

Location: Musée du Louvre, Paris