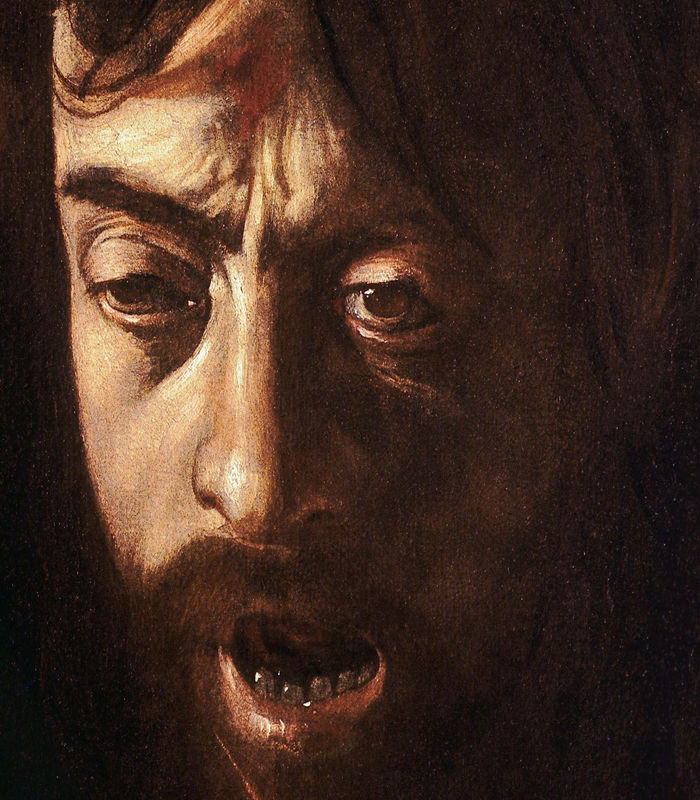

La oscuridad no era para Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio una simple técnica pictórica; era su refugio, su condena y, finalmente, su propia piel. En el ocaso de su vida, acosado por sus demonios internos y por la justicia de los hombres, el genio del tenebrismo nos entregó una de las piezas más perturbadoras y lúgubres de la historia del arte: David con la cabeza de Goliat. Pero tras la superficie de este lienzo barroco no solo hay pintura, hay una confesión de asesinato bañada en sangre y sombras.

Un genio entre sombras y peleas callejeras

Para entender el horror que emana de esta obra, debemos comprender al hombre que sostenía el pincel. Caravaggio no era el típico artista de academia que buscaba la belleza idealizada. Él encontraba la verdad en los callejones más bajos de Rom

Darkness was not a mere pictorial technique for Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio; it was his refuge, his condemnation, and ultimately, his own skin. In the twilight of his life, haunted by his internal demons and by human justice, the genius of tenebrism delivered one of the most disturbing and somber pieces in art history: David with the Head of Goliath. But beneath the surface of this Baroque canvas lies not just paint, but a confession of murder bathed in blood and shadows.

A Genius Among Shadows and Street Fights

To understand the horror emanating from this work, we must understand the man who held the brush. Caravaggio was not the typical academy artist seeking idealized beauty. He found truth in Rome's lowest alleys, among prostitutes, beggars, and criminals. His life was a whirlwind of violence and genius that reached its breaking point one May night in 1606. During a brawl over a bet on a tennis match, Caravaggio killed a man named Ranuccio Tomassoni.

From that moment on, the artist's life became a desperate flight. Sentenced to death by decapitation in Rome, any who found him could carry out the sentence and collect the reward. Caravaggio became a shadow wandering through Naples, Malta, and Sicily, carrying the weight of guilt and the constant terror of losing his own head.

The Painting That Is a Plea for Forgiveness

It is in this context of agony and persecution that David with the Head of Goliath was born. It is not just a biblical representation; it is the most visually striking suicide note ever created. Caravaggio painted this work to send it to Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the man who had the power to grant him papal pardon and allow him to return to Rome. The hidden message between the brushstrokes was as brutal as it was direct: Here is my head, I have already paid my debt.

What makes this painting unique and visceral is the choice of models. Caravaggio did not look for anonymous faces to represent good and evil. In an act of unprecedented technical and psychological audacity, the artist created a double self-portrait. The young David, holding the sword with a mixture of disgust and pity, represents the young and innocent Caravaggio he once was. In contrast, the head of Goliath, dripping with fresh blood and with eyes lost in the void of death, is the current Caravaggio: the murderer, the monster, the condemned man.

The Anatomy of Decapitated Horror

If we look closely at Goliath's face, the mastery of dark Baroque reaches almost unbearable levels. Caravaggio painted himself as the defeated giant, but there is no heroism in his fall. The eyes are dull, fixed on a vision that no longer belongs to this world. The mouth remains half-open, as if taking a final agonizing breath before life definitively escaped through the severed neck.

Unlike other depictions of David and Goliath, where the young warrior is shown triumphant, here David seems overwhelmed by sadness. He gazes at the remains of his enemy with a compassion that hurts. It is the confrontation of a man with his own past and his sins. The sword David holds is inscribed with a Latin phrase that summarizes the essence of the work: H-AS OS, an abbreviation for "Humilitas occidit superbiam" (Humility kills pride).

The Legacy of a Man Who Painted Himself Dying

Caravaggio never knew if his bloody plea was successful. He died under strange circumstances on a beach in Porto Ercole while trying to return to Rome with the pardon in hand. What he left us was this dark mirror where art and life merge in a terrifying way. He did not use models to portray horror; he used his own fear of being executed.

Today, when we contemplate David with the Head of Goliath, we are not looking at a simple religious scene. We are witnessing the final judgment of a man who decided to flay his soul before the world. His agonizing gaze continues to haunt us from the canvas, reminding us that the most fearsome monsters are not those of legends, but those we feed ourselves in the darkness of our actions.

THE WORK

David with the Head of Goliath

Year 1609-1610

Artist Caravaggio

Technique Oil on canvas

Style Baroque

Size 125 cm × 101 cm

Location Borghese Gallery, Rome, Italy