Zeus, the sovereign of Mount Olympus, the one who wields the thunderbolt and rules the sky, was the most powerful god, but also the most prolific. His insatiable appetite for love—whether with goddesses, nymphs, or mortal women—made him the father of a vast progeny. This is not a simple biographical detail; Zeus's offspring is, in essence, the structure upon which all mythology, theater, and art of Western civilization are based. Each of his children, whether Olympian gods or mortal heroes, represents a fundamental facet of human and divine existence.

The Creative Fury of Olympus: Zeus and His Endless Lineage

Zeus's lineage is conceptually divided into two major categories, each with a distinct narrative purpose: the divine offspring, born of other goddesses to ensure cosmic order and the stability of Olympus, and the demigod offspring, born of mortals, whose destiny is suffering, tragic glory, and direct contact with humanity. This duality between divine perfection and mortal imperfection is the driving force behind much of figurative art.

The Pillar of Order: Children Born of Goddesses

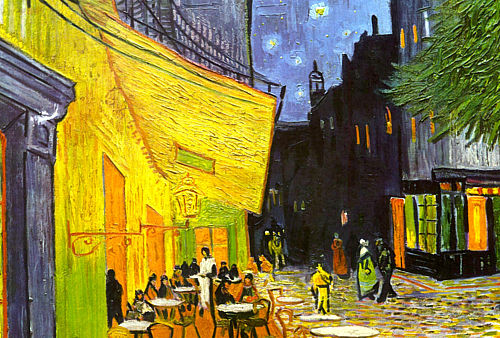

When Zeus united with a deity, the result was the consolidation of a fundamental principle of the universe. The history of his legitimate or divine offspring is both a genealogy and a hierarchy of power. Athena is the most unique daughter and, for many, the favorite. She was not born from a womb, but emerged fully formed, armed, and adult from Zeus's head, after he swallowed her mother, the Oceanid Metis (Wisdom), to prevent the prophesied son from overthrowing him. Athena is not only the goddess of strategic warfare—in contrast to Ares, who represented savage warfare—but also of wisdom, the arts, craftsmanship, and civilization. Her birth represents the victory of reason and planning over brute force. In art, from Phidias to Bouguereau, Athena is always represented as a figure of great serenity and intellectual authority, bearing her aegis and helmet.

Continuing with the divine lineage, we find Apollo and Artemis, the twins of light and the moon, children of Zeus and Leto, a Titaness. Their birth was a dramatic event, as the jealous Hera relentlessly pursued Leto until she found refuge on the floating island of Delos. Apollo, god of the sun, prophecy, music, poetry, and healing, is the epitome of the classical Greek ideal: beauty, order, and moderation. His influence on art, through sculptures like the *Apollo Belvedere*, became the model for the ideal male body during the Renaissance and Neoclassicism. His twin sister, Artemis, goddess of the hunt, wild animals, the moon, and virginity, is a symbol of untamed nature and feminine independence. She is often depicted with a bow and arrows, in a dynamic movement that evokes speed and grace.

Hermes, son of Zeus and the nymph Maia, is the mediator of the pantheon, the messenger of the gods, god of commerce, travelers, thieves, and, crucially, the psychopomp—the guide of souls to the underworld. His speed and cunning made him a nexus between Olympus, Earth, and Hades. In art, he is immediately identified by his winged sandals (*talaria*) and his caduceus, symbolizing rapid transit across all boundaries.

The Human Lineage: Demigods and Tragic Heroes

The second category, the children of Zeus with mortal women, is perhaps the most fascinating, for it introduces imperfection, tragic fate, and the possibility of glory into the human DNA. Zeus assumed countless forms to seduce mortals (a swan for Leda, a shower of gold for Danaë, a white bull for Europa), a narrative device that underscores human weakness in the face of divine power.

Heracles: Strength and Suffering

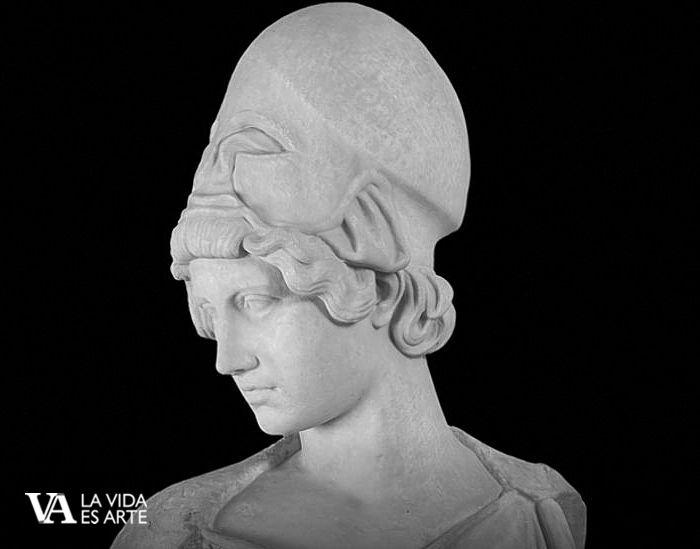

The most famous of all demigods is **Heracles** (Hercules to the Romans), son of Zeus and the mortal Alcmene. His birth was immediately marked by the wrath of Hera, which defined his entire life as a series of labors and sufferings. Heracles is the quintessential hero, whose brute strength is placed at the service of justice, but who is also prone to anger and error. The iconography of Heracles is massive, spanning from the Laocoön to the metopes of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In art, his "Twelve Labors" offer an unparalleled visual repertoire, always depicting him with hypertrophied musculature and wearing the Nemean lion's skin. His constant struggle and eventual apotheosis (ascent to Olympus) served as a powerful moral model for antiquity: the man who, through relentless effort and pain, can achieve divinity.

Perseus: Destiny and Adventure

Another crucial hero is **Perseus**, son of Zeus and Danaë, whom the god visited in the form of a shower of gold. The myth of Perseus is the quintessence of adventure, marked by the fulfillment of a prophesied destiny: the death of his grandfather Acrisius. Perseus is famous for beheading Medusa, rescuing Andromeda, and founding Mycenae. Renaissance sculptures, such as Cellini's *Perseus with the Head of Medusa* in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, capture his heroism at the moment of victory, with an elegance that contrasts with the brutality of Heracles. Perseus represents cunning and divine intervention guiding heroic action.

Dionysus: The Transition to Divinity

Mentioned previously, Dionysus, son of the mortal Semele, deserves a second look in this context. His existence straddling both worlds is crucial. The double birth, being rescued from his mother's womb and gestated in Zeus's thigh, symbolizes the struggle for divine acceptance. His myth is less about strength and more about cultural influence and ecstasy. In art, representations of Dionysus (often young, beautiful, androgynous) and his retinue of Maenads and Satyrs illustrate the liberating, and sometimes destructive, power of the Dionysian spirit over reason.

Helen of Troy and Minos of Crete: Beauty and Law

The list of mortal children is immense, and each left a mark: **Helen of Troy**, daughter of Leda (whom Zeus seduced as a swan), was the woman whose beauty unleashed the greatest war in mythology, a symbol of aesthetic fatality. **Minos**, son of Europa (whom Zeus seduced as a bull), became the legendary king of Crete and, later, one of the three judges of the underworld, symbolizing Zeus's link to earthly law and order.

The Artistic Legacy of Zeus's Lineage

Western art has drawn sustenance from these genealogies because the stories of Zeus's children are the expression of the great human archetypes. Classical and Hellenistic sculpture sought to capture the *Areté* (excellence) of these figures: the imperturbable calm of an Apollo, the excessive, suffering strength of a Heracles, and the intellectual purity of an Athena.

During the Renaissance, artists rediscovered the aesthetic and moral value of these narratives. Michelangelo not only sculpted a *David* but was steeped in the monumentality of Heracles' figures. The Baroque, with its love for drama and movement, reveled in the hunts of Artemis and the orgies of Dionysus. Even modern art has reinterpreted the trauma and ambition of these demigods.

The progeny of Zeus is a catalog of the forces that govern the cosmos: from light and wisdom to adventure, tragedy, and unrestrained passion. By rendering his children in marble and on canvas, artists not only represented a myth but also defined the boundaries of humanity and divinity, ensuring that the lineage of the King of Olympus continued to rule the imagination of Western civilization.