Within classical mythology, there are two figures that often inhabit the same shadowy forests and the same wild legends, yet we frequently confuse them as if they were the same being. We are talking about the faun and the satyr. Although both are closely linked to the cult of Dionysus, the god of wine and ecstasy, their origins and natures hide fundamental differences that define how art has portrayed them throughout the centuries. Today, we will explore these differences through one of the most controversial works in the history of sculpture: James Pradier’s Satyr and Bacchante.

To understand the fascination and rejection this work provoked in its time, we must first clear the mythological mist. The satyr is a purely Greek creature. In ancient literature and art, it is described as a being that is half-man and half-goat, characterized by uncontrollable lust and an image that many considered vulgar or outright unpleasant. The satyr is not a gentleman of the woods; it is the representation of the lowest instincts, a being with hooves, a horse's tail, and a sexual aggressiveness that kept it always on the lookout for nymphs and human women.

The faun, by contrast, belongs to Roman mythology. Although it shares the horns on its head, its lineage is different: it is half-man and half-deer. This heritage gives it a much more elegant, calm, and simple profile. While the Greeks saw in the satyr the danger of losing control, the Romans considered fauns to be the representation of the very fear one feels when venturing into distant lands or virgin forests. The faun watches you from the thicket; the satyr pursues you in the midst of Dionysian frenzy.

Dionysus (or Bacchus to the Romans) rarely traveled alone. His retinue, the thiasus, was composed of these hybrid beings and the bacchantes. The latter were mortal women who, possessed by the god, abandoned their homes to surrender to rituals of dance, wine, and ecstasy in the mountains. They are often confused with the maenads, who were the divine nymphs serving the god, but the bacchantes represented the real danger of how divinity could strip a common woman of her sanity.

James Pradier and the Salon of 1834

We jump forward in time to early 19th-century France. James Pradier, a highly talented Swiss-French sculptor, dominated the scene with a neoclassical style, but with a twist that made him unique: an evident and disturbing erotic charge. In 1834, Pradier presented his work Satyr and Bacchante at the prestigious Paris Salon. What was meant to be just another mythological representation turned into a national scandal that forced the French government to refuse its acquisition, deeming it morally dangerous.

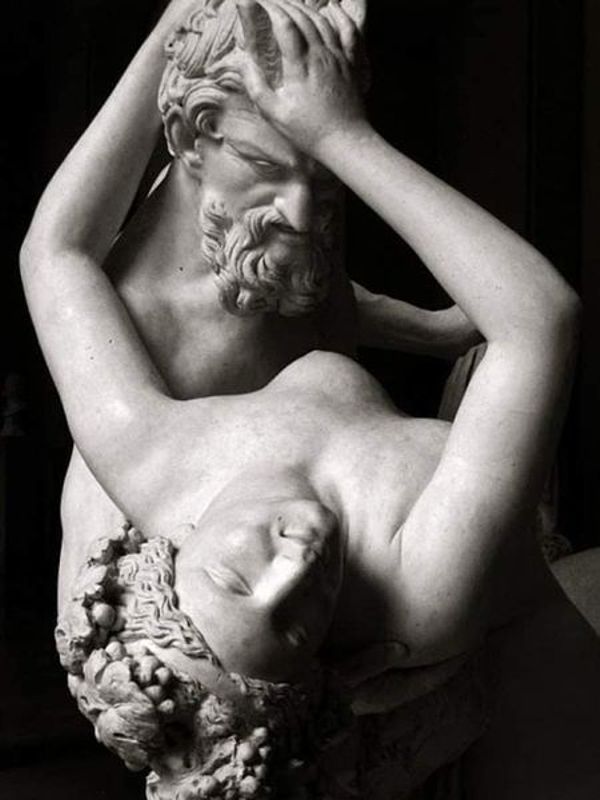

What was it that so upset the academics and the public of the time? It wasn't just the nudity, as neoclassical art was full of it. The problem was the fleshly realism. Pradier did not sculpt an idealized scene of distant gods; he sculpted an encounter that felt too real, too human, and too close. The sculpture exudes a palpable eroticism: we see a Bacchante crowned with vine leaves who seems to have completely abandoned her senses, surrendering to the arms of a satyr who discovers her with a mixture of curiosity and animal desire.

The piece was confined to a small separate room during the Salon, an attempt at censorship that only served to ensure no one wanted to miss it. The scandal reached such a point that a foreign buyer, Count Anatole Demidoff, had to appear to save the work from ostracism and take it to his palace in Italy. But the real gossip of the time lay in the faces of the figures.

Juliette Drouet: The Muse of Discord

Many of Pradier's contemporaries believed they recognized the features of Juliette Drouet in the bacchante, an actress and model famous for her beauty and her turbulent love life. Juliette was Pradier's lover at the time, and they even had a daughter together. The fact that the sculptor used his lover to represent a woman in full Dionysian ecstasy under the hands of a satyr was seen as a public confession of his private life.

Juliette’s story does not end there. Shortly after, she would become the loyal and legendary lover of the writer Victor Hugo, whom she accompanied for decades. The scandal was also fueled by the idea that the satyr itself could be a critical self-portrait of the sculptor, although modern experts suggest that the satyr's face follows ancient statuary models instead. Even so, the connection to Juliette Drouet was so strong that even Count Demidoff, who ended up buying the statue, had also been romantically linked to her. In the Paris of 1834, the work was not just art; it was the center of a love triangle (or square) that fueled all the newspapers.

Breaking with Idealism: The Power of Naturalism

Beyond high-society gossip, Satyr and Bacchante is a fundamental work because it announces the end of Romanticism and the most rigid Neoclassicism. Pradier decided to ignore idealized Greek beauty—the kind that softens forms to make them appear divine—and opted for a meticulous naturalism. If you observe the sculpture closely, you will see that the artist detailed every fold of the skin, every muscular tension, and every texture.

One of the most striking contrasts in the work is the juxtaposition of textures. The girl's human foot, soft and delicate, rests right next to the satyr's coarse, cloven hoof. The realism of the skin on the bacchante's back, pressed against the hairy, rough thigh of the hybrid being, creates a tactile sensation that the viewer can almost feel. Pradier didn't want us to admire the statue; he wanted us to feel the difference between human civilization and the brute force of nature.

The scale of the work, life-sized, adds a layer of realism that is intimidating. Standing before it, the scene stops being a legend written in a book and becomes an event happening right before our eyes. It is this brute force and unfiltered sensuality that ensures, even today, that the work leaves no one indifferent as they walk through the galleries of the Louvre Museum.

A Journey to the Louvre

For those who wish to experience these contrasts in person, the destination is Paris. In the Louvre, Pradier's sculpture continues to remind us that art does not always seek peace or spiritual reflection; sometimes, its mission is to shake our instincts, remind us of our animal past, and show us that beauty can also be found in imbalance and unrestrained passion.

The Satyr and Bacchante is, ultimately, a testament to an era when art began to dare to be too real. It is the bridge between the order of classical marble and the disorder of the deepest human emotions. A work born of scandal, it survived thanks to private collecting and today remains as a beacon of erotic naturalism in one of the most important museums in the world.

THE WORK

Satyr and Bacchante

Artist: James Pradier

Year: 1834

Style: Neoclassicism with naturalistic tendencies

Material: Marble

Location: Louvre Museum, Paris