The Madonna of the Magnificat, created by the Florentine genius Sandro Botticelli between 1481 and 1485, is not merely a painting; it is a window into the soul of the Renaissance. This period, a time of revolution in art, science, and philosophy, was characterized by an explosion of interest in classical culture, ancient wisdom, and, above all, a deep exploration of human dignity and its relationship with the divine.

Botticelli, with his unmistakable style and his ability to capture an almost melancholic, ethereal beauty, sought to transcend simple religious representation. His goal was to capture an image of spiritual perfection, the tenderness of maternal love, and the crucial role of faith in human life. The Madonna of the Magnificat embodies this vision, merging religious piety with the allegorical elegance of grace and Humanist virtue.

This masterpiece has its roots in 15th-century Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance. It was commissioned for the most powerful and influential family of the era: the Medici. The Medici were not just bankers; they were relentless patrons who shaped the art and culture of their city. By promoting artists like Botticelli, they encouraged a break from the rigid traditions of medieval art, paving the way for the exploration of human emotions, profound spiritual feelings, and an idealized beauty that sought perfection in form. This context of patronage and the pursuit of ideal beauty permeates every brushstroke of the painting.

The work stands out for its format: a tondo, which means "round" in Italian. This circular shape was very popular for private works intended for devotion in the homes of wealthy families, symbolizing eternity and divine perfection. At the exact center of the composition, we see the Virgin Mary tenderly holding the Christ Child. Both are surrounded by five angels in poses of adoration and assistance. The intense colors, fluid forms, and expressive faces make this painting one of the most admired works in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

The Song of Praise: The Virgin and the Magnificat

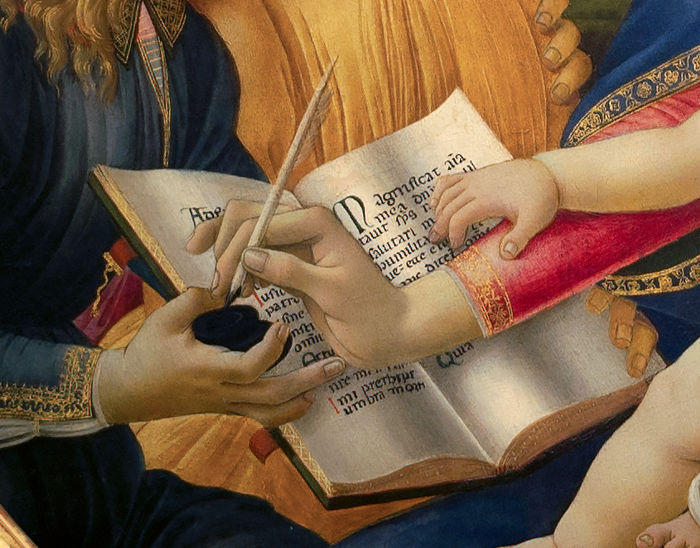

The figure of the Virgin Mary dominates the center, depicted as a serene, pious young woman overflowing with grace. Her attire is a study in chromatic symbolism: she wears a rich blue cloak, the color traditionally associated with purity, the heavens, and divinity, superimposed over a red dress, which prefigures the sacrifice and passion that her son's life will bring. Mary's position is unique: she is holding a pen while writing in a book, the Magnificat.

The Magnificat is the canticle of praise that Mary sings in the Gospel of Luke (1:46-55) when she visits her cousin Elizabeth and her divine election is confirmed. By depicting her writing, Botticelli captures a moment of deep spiritual introspection. Mary is not only the mother but also a wise and literate woman, a model of devotion, faith, and, above all, humility. In this gesture, the artist elevates the Virgin, making her an intellectual figure as well as a spiritual one, combining human wisdom with divine faith.

The Christ Child, seated in Mary's lap and supported by her, looks upwards with an expression that goes beyond mere infancy. There is a calmness and wisdom in his eyes that suggest a premonitory understanding of the sacrifice that awaits him. This contrasts with the typical naive portrayal of the Bambino. Here, Jesus is both a child seeking refuge with his mother and a divine entity aware of his destiny. His soft golden tunic reinforces his divine nature and sacred lineage.

Symbolism and Composition in the Tondo

Surrounding the central pair, Botticelli has painted five angels with a mixture of sweetness and solemnity. These angels fulfill crucial functions beyond mere companionship: they are living symbols of divine adoration and protection. Two angels on the left hold the book where Mary writes, while two others crown the Virgin with a stellar headdress.

The crown of stars is a detail of immense symbolism. In Christian tradition, stars represent the celestial connection, and the crown itself symbolizes Mary's status as the Queen of Heaven. The hands of the angels and the Virgin are arranged in an almost interwoven pattern, creating a circle of unity and harmony that emphasizes the perfect connection between heaven and earth. The fact that an angel helps hold the book reinforces Mary's role as an intercessor, a figure connecting God and humanity.

The tondo format (circular) is not accidental. It reinforces the sense of a timeless and perfect scene, without beginning or end. Botticelli uses the circular shape to continuously guide the viewer's gaze around the central figure, creating an enveloping movement that accentuates the intimacy of the moment. The background, where a serene landscape is glimpsed through an arched window, serves to anchor the sacred scene in an earthly but idealized world, while the golden vases and the overall elegance of the setting recall that the work was intended for a noble and sophisticated court.

The Mastery of Color and Ethereal Light

Botticelli is a master in using color to evoke emotion and spirituality. In this work, the warm skin tones, the intensity of the red and blue pigments, and the golden highlights of the angels' hair and the crown converge to create an atmosphere of deep peace and serenity. The deep ultramarine blue of Mary's cloak, an expensive and valued pigment in the Renaissance, not only symbolizes divinity but was also a way to honor the status of the Medici family who commissioned the work.

The light used by Botticelli is perhaps his most important signature. It is a soft, diffuse, and enveloping light that seems not to come from an external source, but to emanate from the figures themselves. By eliminating harsh shadows and dramatic contrasts, any sense of earthly weight is nullified. This gives the scene an almost ethereal and supernatural quality, as if the characters exist on a spiritual plane, perpetually illuminated by the divine presence.

The Legacy of the Magnificat

The title and the central focus of the work, Mary's canticle, are essential. The Magnificat is a deeply social and revolutionary text. In it, Mary glorifies God, not only for her own blessing but also for His justice: "He has brought down the mighty from their thrones, and exalted those of humble estate; he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty." This canticle has historically been interpreted as a powerful expression of hope for the dispossessed and oppressed.

By having Mary write these words, Botticelli underscores her role as a prophetess and a figure of wisdom. The scene is not static; it is a reminder that faith is not just contemplation, but also action and recognition of divine justice. This combination of sublime art with a message of hope and humility resonated deeply within the intellectual and religious climate of Renaissance Florence.

Botticelli: The Artist of Idealized Beauty

The Madonna of the Magnificat remains one of Botticelli's most admired and reproduced works, reflecting the peak of his unique style. Unlike contemporaries who focused on scientific perspective and anatomy (like Leonardo da Vinci), Botticelli concentrated on the idealization of spiritual beauty and the purity of the soul. His figures are graceful, with flowing hair and expressions of dreamy sweetness that evoke profound serenity.

His art became synonymous with Florentine grace, and this particular work is a testament to the artist's deep religious devotion. The Madonna of the Magnificat is not just a representation of a mother and her child; it is an exploration of what pure love, unwavering devotion, and the mystical connection to the divine mean. Today, it remains a beacon of the idealized beauty of the Renaissance and a reminder that true nobility resides in humility and spiritual love.

THE WORK

Madonna of the Magnificat

Year: c. 1481-1485

Artist: Sandro Botticelli

Medium: Tempera on panel

Style: High Florentine Renaissance

Size: 118 cm (diameter)

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy