The sea and the foam: two essential elements upon which artistic representations linked to the birth of Aphrodite are based. Throughout the centuries, artists have offered a very free interpretation of the details of the myth, but always returning to that aquatic origin. From this arises the epithet "Anadyomene," which literally means "rising from the breast of the waters." However, it is curious to note that representations staging the violent emergence or the actual movement of the goddess rising are truly rare. Most painters prefer the moment of calm after the storm.

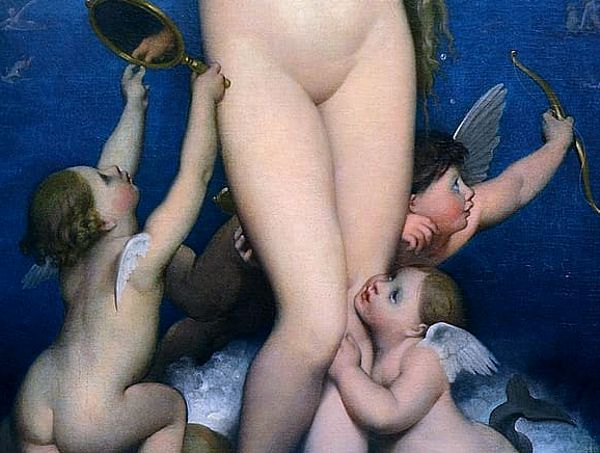

Most Venuses described as Anadyomene by artists are women who have already completed their emergence from the waters. They are depicted standing, naked, and offering observers all their grace in a state of almost divine stillness. The work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres is particularly emblematic of this type of representation. It consists of a narrow vertical frame in which the young woman occupies the absolute center, becoming the axis of the universe. The goddess appears upon a foamy surface, combing her hair in a position that allows for the maximum stretching of her body and, of course, her total unveiling before our eyes.

Forty Years Seeking Perfection

What makes this work fascinating is not just what we see, but the time it took Ingres to finish it. The painter began the first sketches in 1808, while he was in Rome, but he did not finalize it until 1848. Forty years of retouches, doubts, and adjustments! This slowness speaks to Ingres's obsession with the perfect line. For him, color was secondary; what mattered was the drawing, the curve that defines anatomy, and that skin that looks as if it were made of porcelain or ivory.

Ingres was not seeking photographic realism. If you look closely at the anatomy of his Venus, you will notice it seems almost impossible: the arms are extremely long, the hips have an idealized curve, and the skin lacks any human imperfection. Ingres wanted to paint an idea of beauty, not a real woman. He wanted his Venus to be the sum of all possible beauties, a concept the Greeks called "kalokagathia" (that which is beautiful is necessarily good).

The Court of Little Lovers

The lower third of the canvas is crowded with putti—those little cupids who seem to flutter in a frenzy of adoration. These mythological beings are not there just for decoration; they emphasize the divinity of the protagonist. Some admire her with devotion, others kiss her feet as a sign of submission, and one of them prepares to shoot an arrow, reminding us that the love this goddess inspires is often an unavoidable wound. Meanwhile, the goddess shows a placid attitude, oblivious to the childish chaos occurring at her feet, absorbed in the ritual of her own birth.

It is interesting to observe how these little cupids contrast with the static verticality of Venus. While she is a column of calm, the putti are pure movement and emotion. This inverted pyramidal composition (with the base full of figures and the top centered on a single one) guides the viewer's eye directly toward the face of the goddess, who gazes into nothingness with that expression of "divine indifference" so characteristic of Neoclassicism.

The Nude as a Sacred Pretext

The work perfectly illustrates the function of the goddess in art history: a hymn to beauty and love. Representing Aphrodite or Venus, and even more so the moment of her birth, was the perfect pretext for artists to depict the female body in its nakedness without facing the moral censorship of the time. If you painted an ordinary woman naked, you could be branded as obscene; if you painted a goddess, you were creating "classical culture."

It is curious to remember that in early Greco-Latin antiquity, goddesses were usually depicted clothed. Athena wore armor, Hera heavy robes, and Artemis her hunting gear. However, Aphrodite, by virtue of her quality as the goddess of love and sexuality, became the only female deity who could legitimately be represented nude. Ingres takes full advantage of this tradition, removing any trace of clothing or jewelry, allowing the goddess's own skin to shine against the deep blue of the sea and sky.

Ingres Against the World: The Struggle for the Ideal

During the period Ingres worked on this Venus, the art world was changing. Delacroix's Romanticism, with its loose brushwork and violent dramas, was gaining ground. Ingres, however, remained the great defender of order and purity. For him, this Venus Anadyomene was a declaration of principles. In a world that was starting to love disorder, he offered symmetry. In a world that loved muddy and emotional color, he offered smooth surfaces and clear colors.

Today, when we see this work in the Musée Condé, its modernity surprises us. That way of treating the human body as if it were a polished marble sculpture later influenced artists as diverse as Picasso or the fashion photographers of the 20th century. Ingres taught us that the nude is not just flesh, but an architecture of curves and lights designed to captivate the soul through the eyes.

The Venus Anadyomene remains, centuries later, a reminder that beauty, even if born from the ephemeral foam of the sea, can become eternal if an artist has the patience to pursue it for forty years.

THE WORK

Vénus Anadyomène

Artist: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Year: 1808-1848

Technique: Oil on canvas

Style: Neoclassicism

Size: 163 × 92 cm

Location: Musée Condé, Chantilly, France