Size matters. This is a deeply rooted belief in modern times and contemporary culture, where physical vigor, overflowing virility, and power are often associated with magnitude. We live in an era of hyperbole, where big automatically translates to better. However, this concept was radically opposite for the ancient Greeks, the very people who laid the foundations of our civilization, our politics, and, of course, our concept of beauty. In classical Greek art, most traits of a great man —a hero, a titan, a god, a warrior— were represented as developed, firm, and harmonious, from their muscular torsos to their serene features. So, why weren't these same aesthetic principles applied to their genitals?

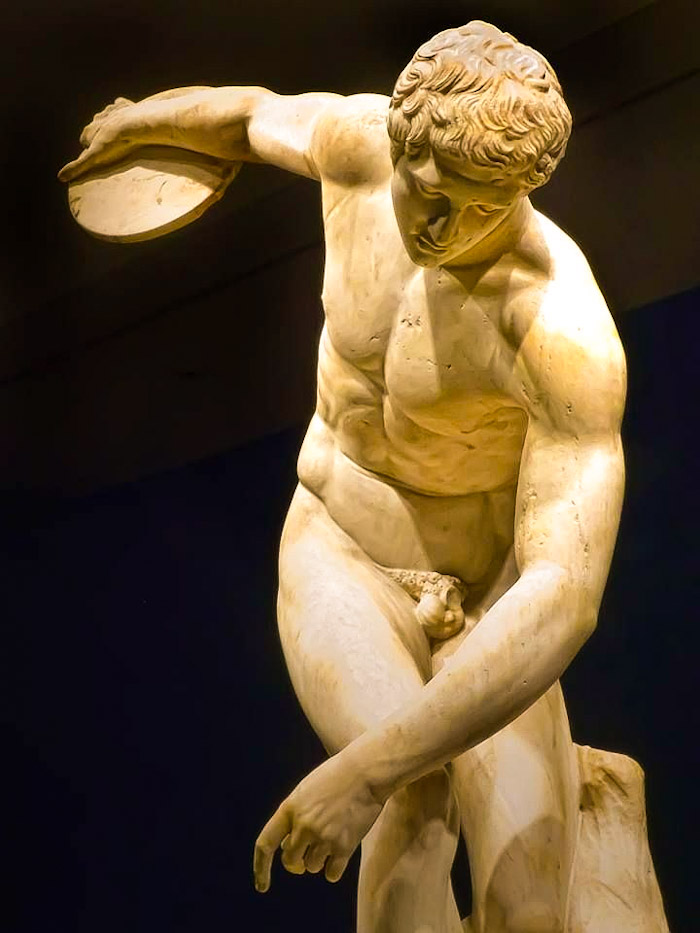

To the contemporary eye, accustomed to the canons of the entertainment industry and a modern obsession with hyper-masculinity, the bodies of Greek statues are the pinnacle of athletic perfection, except for one strikingly small detail. Sculptures of illustrious and powerful men, showing burly figures with tense, undulating muscles that look ready for battle or Olympic competition, often sport modest or even very small penises compared to the human average. This visual discrepancy often generates nervous laughter or confusion in the halls of the world's most famous museums.

This particularity has surprised countless contemporary art lovers and historians, who see a seeming contradiction between the massive bodies and the mythically great personalities that accompany these figures, from the imposing Zeus to the most celebrated athletes of antiquity. Far from being an artist's oversight, a lack of anatomical knowledge, or a statement of self-censorship out of modesty, this aesthetic choice is a profound, deliberate cultural statement loaded with philosophical symbolism. In Ancient Greece, the body was the mirror of the soul, and every inch of sculpted marble had a reason for being that went far beyond simple appearance.

Sophrosyne: The Virtue of Self-Control

To truly understand this aesthetic choice, we must take a mental journey back to the ancient Greek world around 400 BC. Back then, standards of desirability were radically different from ours. Large, erect penises were not considered a sign of power, nobility, or strength. In fact, for the intellectual and warrior elite of Athens or Sparta, possessing a large-sized member was viewed with suspicion, if not direct contempt. The small, flaccid penis was in total harmony with the highest Greek ideals of masculine beauty, civility, and, above all, moderation. It was a badge of the highest culture and a model of civilization against barbarism.

The key concept governing this aesthetic is sophrosyne, one of the cardinal virtues of Greek philosophy. Sophrosyne is a complex term that has no simple, direct translation, but is commonly associated with moderation, self-control, prudence, and temperance. It represented a man's supreme ability to control his emotions and, most crucially, his instincts and carnal appetites. For an educated Greek, a man who acted under the influence of blind passion, unrestrained desire, or voracious appetite was not a free man, but a slave to his own animal impulses. He was considered barbaric, uncivilized, and inferior.

Therefore, in art, the size of the phallus did not function as an index of sexual potency or fertility, but as an index of character and moral quality. A small penis in a resting state visually communicated that the man's mind, his intellect (logos), dominated his more basic impulses (pathos). Gods, heroes, philosophers, and athletes, embodying physical and mental perfection, had to show absolute moderation. Their small members essentially represented the definitive victory of human reason over the animal instinct that resides in all of us. The Greek hero was one capable of maintaining calm even in the heat of battle or in the face of the most seductive temptation.

The Dramatic Contrast: Satyrs and Barbarians

To reaffirm this ideal of moderation and leave no doubt in the viewer's mind, Greek art used dramatic and visually striking contrasts. If you wanted to know what the Greeks thought of excess, you only had to look at who they represented with large attributes. Large-sized penises were reserved exclusively for figures who embodied precisely the lack of control and the absence of civilization.

Satyrs are the clearest example. These mythical creatures, represented as half-man and half-goat or horse, were the personification of lust, drunkenness, and depravity. They were beings who lived in the forests, outside the laws of the polis, and perpetually dedicated to the pursuit of physical pleasure. In vases and reliefs, satyrs consistently appear with enormous and often erect genitals, sometimes of comic or grotesque proportions that reached almost to their chests. These creatures totally lacked sophrosyne; they were dominated by their lowest instincts. Their large endowment was the graphic symbol of their bestiality, their zero intellectual capacity, and their inability to integrate into sophisticated Greek society.

In addition to satyrs, excessive size in Greek art was systematically associated with other negative traits that any respectable citizen wanted to avoid:

- Stupidity and Ridicule: In Greek theater, especially in comedy, foolish characters, buffoons, and low-intellect slaves often wore large artificial genitals over their tunics. This served as an immediate visual signal to the audience that the character lacked the capacity for logical reasoning. The large phallus was, literally, a comic and degrading attribute.

- Barbarism and the Enemy: The Greeks considered themselves the center of reason. The concept of "barbarian" applied to anyone who did not speak Greek and did not share their values of moderation. In some representations, foreign enemies, such as Egyptians or Persians, were portrayed with larger phalluses to symbolize their supposed wild and undisciplined nature, ruled by the senses and not by critical thinking.

- Old Age and Decay: Curiously, in certain contexts, a large phallus could also represent the loss of youthful vigor and the entry into a stage of physical decay where the body no longer responds to the will of the mind, representing another form of loss of harmony and control.

In this way, satyrs, fools, and enemies served as a dark mirror. If large phalluses represented disordered appetites and uncontrollable passions that degraded the human being, then the small and discreet penis represented the pinnacle of self-control, elegance, and superior intelligence. Size was, in essence, an ethical code sculpted in stone that reminded every citizen that their value resided in their brain and discipline, not in their anatomy.

Proportion and Harmony: The Canon of Polykleitos

Beyond morality, the choice of size was also deeply linked to the technical principles of proportion and harmony that defined classical art, especially from the teachings of Polykleitos in the 5th century BC. For Greek sculptors, the human body was not to be portrayed with raw or photographic realism, but was to be a manifestation of mathematical idealism. The universe was ordered by numbers and proportions, and the hero's body had to reflect that cosmic order.

The goal of a sculptor like Phidias or Polykleitos was to create a work where every part of the body held a perfect relationship with the whole. An erection or a disproportionately large penis not only violated the philosophical principle of sophrosyne but also visually destroyed the symmetry of the whole. In a classical sculpture, the viewer's eye must travel along the lines of the body without sharp interruptions.

For these artists, beauty resided in subtle balance. A small, resting penis integrated almost invisibly into the general anatomical composition. This allowed the viewer to focus on what really mattered in defining a hero: the almost divine serenity of his face, the perfect tension of his pectorals, the strength of his legs, and his noble posture (contrapposto). A large phallus would have been a fatal visual distraction, transforming a work of art intended for spiritual elevation into an object of sexual fixation or, worse, a parody. Classical Greek art sought transcendence, not excitement.

Legacy and Persistence of the Ideal: From the Renaissance to Today

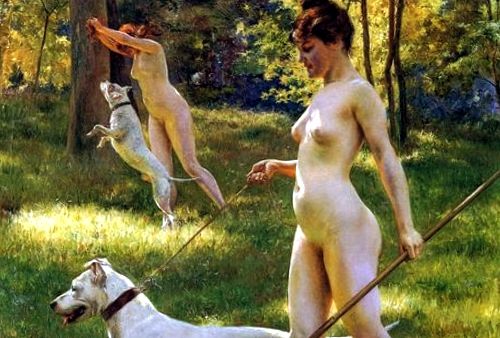

This aesthetic ideal did not die with the fall of the Greek city-states. It remained surprisingly consistent during the Hellenistic period and decisively influenced Roman art, which absorbed and replicated these masterpieces. Centuries later, during the Renaissance, artists of the stature of Michelangelo took up these same principles. If we look at Michelangelo's famous David, we will notice that it follows exactly the same logic: a powerful and monumental body with modest genitals. Michelangelo was not being shy; he was paying homage to the Greek concept that David, a man of faith and intellect who defeats the brute force of Goliath, had to show mastery over himself before mastering the giant.

Although the cultural symbolism of the penis has taken a 180-degree turn in modern popular culture, where pornography and marketing have distorted our perception of what is normal and desirable, the lessons of Ancient Greece remain relevant. Today, we continue to associate success with excess, but the Greeks whisper to us from the past that true power is internal.

The representation of the male sex, then as now, is an expression of man's ability to impose himself. However, in antiquity, that domination was not exercised over others through size, but over oneself through will. The true hero was not the most biologically endowed, but the most intellectually disciplined. He was a civilized being, a thinker, and a moral model.

So, the next time you visit a museum, stand before a photograph of a classical statue, or admire the perfection of ancient marble, remember that that small anatomical detail is not a deficiency or a taboo. It is a statement of principles. It is proof that, for the culture that invented democracy and philosophy, true greatness is not measured in inches, but in the capacity to maintain reason over instincts. At the end of the day, the Greek lesson is eternal: size does not matter; what truly honors a human being is the measure of their self-control and the unwavering strength of their intellect.